“Success means being very patient, but aggressive when it’s time.”

Charles Munger

We finished the year with a significant shift in interest rate expectations, a central component of the financial system. With rates having risen substantially over the last two years, the fourth quarter saw an almost palpable sense of relief as investors refocused their attention from the next hike to the first cut. You may recall that this time last year, the market was failing to account for what we felt was a high likelihood of interest rates remaining at higher levels throughout 2023. As it transpired, the market was forced to adjust to this reality as the year progressed. In what follows, we explore what is currently driving market expectations and explain how we are thinking about the year ahead.

The final quarter of 2023 saw inflation continue to fall in developed economies, with consumer prices in the US rising by 3.1% in the 12 months to November compared with a rise of 7.1% a year ago. Whilst the speed of price increases is slowing, a 3.1% rise remains above the Federal Reserve’s inflation target of 2%. Importantly, the core inflation measure in the US, which excludes more volatile food and energy prices, remained steady at 4% in November. This metric captures the ‘sticky’ inflation that central banks are particularly concerned about since it can become self-perpetuating, with rising prices in service sectors resulting in demands for higher wages and so on. For this reason, the year also saw a continuation of interest rate hikes by major central banks such as the Federal Reserve (the Fed), the Bank of England and the European Central Bank. The Fed, for example, lifted its minimum rate from 4.25% to 5.25% over the course of the year.

However, the final quarter of the year saw a significant shift in interest rate expectations as the Fed noticeably softened its rhetoric on the path of monetary policy going forward. Coupled with autumn inflation data that came in below economists’ forecasts, the market took this as a cue for falling interest rates next year, causing bond prices to rise significantly (and their yields to fall), with equities also rallying in response to this prospective loosening of monetary conditions. At the end of December, the bond market was pricing 6 rate cuts by the Fed in 2024, starting as soon as March. Whilst inflation is certainly starting to reflect a cooling economy, which may give central banks the freedom to cut interest rates in the future, we believe that substantial cuts would only come in the event of a US recession, for which the current evidence is mixed.

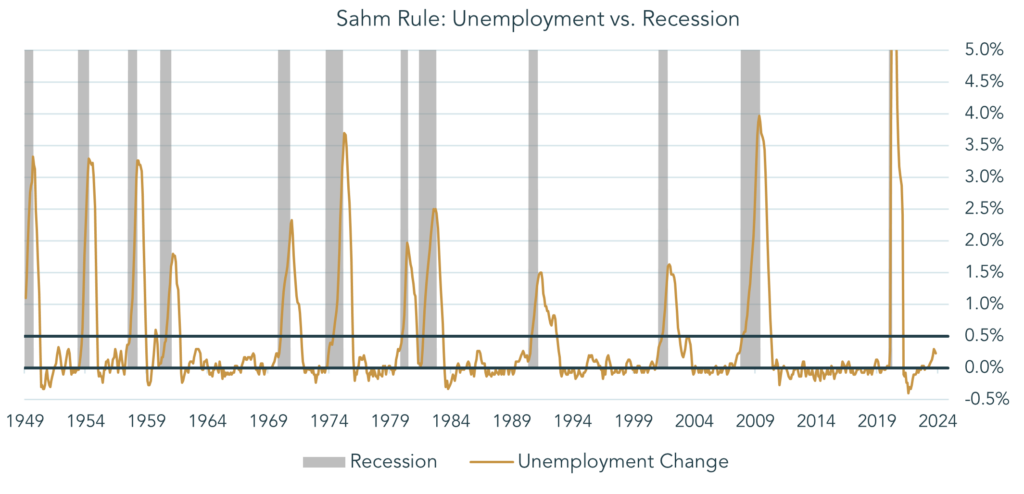

As the Fed itself has said, labour market dynamics are increasingly determining the path of monetary policy. However, being a lagging economic indicator, the latest headline unemployment number is not a particularly helpful guide for investors as to what central banks will do next. Fortunately, there are alternative data sources, such as job vacancies and hiring surveys, that can offer insight into how the labour market is responding to monetary policy. These data suggest that unemployment should continue to creep higher but offer little guidance as to how large or sustained the increase will be. One important framework that can help answer this question is the Sahm Rule, shown in the chart below.

Source: St Louis Fed, National Bureau of Economic Research, 2023

Economist Claudia Sahm argues that once unemployment rises a little bit, it tends to go on to rise a lot as unemployed workers have less money to spend on goods and services, causing other companies to lay off workers in response to weaker sales. Specifically, she identified that the threshold at which recessions have started historically is a 0.5% increase in the three-month moving average of the unemployment rate, relative to its lowest level during the prior 12 months. The chart shows that we have recently been moving towards this 0.5% level but are not there yet. We would conclude from the Sahm Rule that it is too early to say for certain whether we will see the kind of sustained and significant rise in unemployment that would typically occur during an economic recession.

It is certainly possible that monetary policy will continue to squeeze economic activity, causing a deeper downturn as unemployment rises sharply. However, it is also possible that employment will be resilient, preventing the Fed from loosening financial conditions. The Fed and other major central banks are, after all, focused on tackling inflation. If underlying price increases in the service sector, as measured by core inflation, are seen to be causing wage demands to spiral out of control, policymakers will have no choice but to continue to choke the economy with higher interest rates. In this context, US wage growth of 5.2% in November would suggest that the market’s expectations for 6 interest rate cuts in 2024 might be too optimistic. If interest rates were to be cut by less than the market expects, we would see upward pressure on bond yields and corresponding losses for bond investors.

Part of the reason that central banks focus on core inflation is that they have less control over the cost of inputs to the economy, which cause headline and core inflation to differ. The impact that commodity shocks can have on global supply chains, and by association inflation, has been well exhibited by the round trip that resources such as natural gas, wheat and fertiliser have taken since Russia invaded Ukraine in February 2022. With spikes in food and energy prices initially driving elevated inflation across developed markets, the sharp retreat in the prices of some of these commodities, notably energy, became a detractor from inflation towards the end of 2023. With the outbreak of a tragic conflict between Hamas and Israel in October, investors have refocused their attention on the commodities which can stoke inflation.

The moves in the oil price as the war broke out would suggest that traders believe the conflict will be contained, with little immediate impact anticipated on commodity supply chains in the Middle East. However, even if it remains notionally confined to Israel and Gaza, there are some potentially profound second order effects to consider. We have already seen some examples, with Western cargo vessels travelling through the Red Sea attacked by Houthi militants from Yemen in a show of support for Hamas. The attacks prompted the US to take direct military action in the region, with UK and European diplomats expressing a willingness to follow suit at the time of writing. With shipping lanes in the Red Sea handling c.12% of global trade, the inflationary effects of ships and tankers having to take a 5,000-mile detour around Africa could be material.

With a US presidential election due in November, Washington’s diplomatic posture has come into sharp focus, particularly regarding military aid. Some of Ukraine’s allies have been tapering their assistance of its fight against Russia. Whilst the US has maintained its support, with a $250m military package announced by President Biden in December, the proposal was initially blocked by Senate Republicans in a sign that foreign policy is becoming increasingly contentious. The political cost of a foreign policy mistake by President Biden could be large and with tensions rising in the Middle East, the chances of such a mistake are also elevated. The stakes are equally high on the economy, which is another reason we are wary of drawing premature conclusions from the recent uptick in US unemployment. It is very much in Biden’s interests to keep unemployment down and we expect him to pursue this by any means necessary. Indeed, government roles accounted for a meaningful share of the new jobs created in 2023, without which the trend in unemployment would look more negative.

Entering 2024, we find ourselves at a crossroads at which two apparently binary economic outcomes look possible. On the one hand, the labour market may continue to weaken as the economy tips into a recession. On the other, the changes we have seen in financial conditions may prove insufficient to stop the labour market from continuing to spur inflation, causing the Fed to maintain its restrictive monetary policy. It is therefore prudent to remain nimble, incrementally adjusting our portfolios to reflect the changing probabilities of each scenario in order to maximise our potential returns.