“Banking is very good business if you don’t do anything dumb.”

Warren Buffett

This year started with a sharp rally in equity markets. Having entered the year with our portfolios cautiously positioned, including a higher cash balance than we would ordinarily hold, we felt that equity markets were exhibiting exuberance that was somewhat detached from economic reality. We were therefore not surprised to see the equity market fall 7% from its highs in February to its low point in mid-March, although the catalysts for this correction were somewhat unforeseen. What began as an isolated incident at a regional US bank spread via the propagating force of market sentiment to bank equities all over the world. As deposits were withdrawn, the weakest banks were left most exposed, with Credit Suisse the most high-profile casualty of the turmoil. In this letter, we discuss recent events and some areas of opportunity we see in the financial services sector.

The series of events that ricocheted across financial markets began in early March with the failure of Silicon Valley Bank (SVB), a specialist mid-sized US bank with a focus on technology companies and entrepreneurs. The bank enjoyed significant inflows of deposits as the technology sector thrived during the Covid-19 pandemic. In receipt of vast sums of cash, SVB decided to invest in assets such as government bonds and government-backed mortgage bonds with long maturities. As interest rates rose rapidly last year, the value of these assets fell significantly, leaving SVB sitting on more than $17 billion in unrealised losses in this portfolio at the end of 2022. To meet day-to-day cash withdrawals from clients, SVB was forced to liquidate some of these investments at a loss. When SVB disclosed these losses and announced its intention to raise additional equity capital, fear spread among its depositors who sped up withdrawals, leading to a run on the bank.

The nature of SVB’s deposits exacerbated the bank’s problems, as they were often larger than the regulator’s $250,000 limit on deposit insurance. In fact, SVB had over $150 billion in uninsured deposits at the end of last year. With a concentrated client base of wealthy entrepreneurs and large companies worried about their uninsured cash balances, deposits were particularly flighty. Ultimately, the regulators placed SVB into receivership, with the bank’s international subsidiaries also taken over by various entities. The issues at SVB had a knock-on effect on peers with similar business models, like Signature Bank, which also had a significant proportion of deposits above the regulator’s insurance limit and suffered a similar fate to SVB. These two banks were the second and third largest banking failures in US history.

Whilst not operating a comparable business model to these specialist US banks, Credit Suisse has for some time been considered a weak link in the European banking community. As a result, it was dragged into the crisis of confidence as its ultra-high-net-worth clients began withdrawing their deposits at an unprecedented pace. Although Switzerland’s second largest bank may not have been a structurally flawed business model in the way that SVB was, confidence is everything in banking. Once client confidence starts to waver, a bank’s demise can very quickly become a self-fulfilling prophecy. This proved to be the case with Credit Suisse, which was forced by Swiss authorities to combine with its larger Swiss rival, UBS, on what look to be highly favourable terms for the acquirer.

As part of this deal, Switzerland’s regulator mandated a write-down of the lowest-ranking tier of Credit Suisse’s debt, known as Additional Tier 1 bonds (AT1s). Whilst the documentation for these bonds provisioned for such an emergency move, opinions are divided on the legality of the treatment of these bonds. In any case, the actions of Swiss officials resulted in volatility in this pocket of the bond market as investors weighed the long-term implications for these securities. This volatility eased as other European regulators, including the European Central Bank and the Bank of England, quickly distanced themselves from the moves made by the Swiss authorities. Furthermore, the clause in the documentation of Credit Suisse bonds that was relied upon by the Swiss regulator is not present in the AT1s of most other banks.

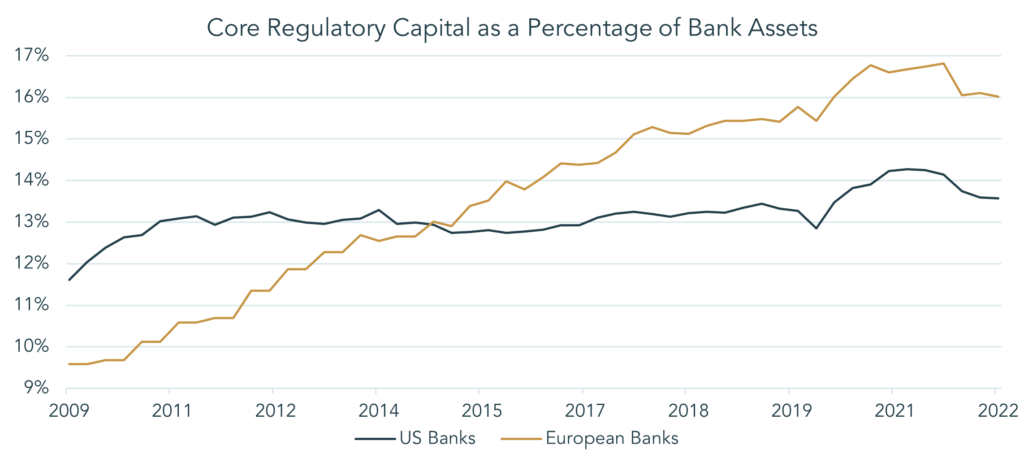

Taking a step back from recent events, we believe that European banks offer a fundamentally different investment proposition to their US counterparts. After the financial crisis of 2008, European banks slowly rebuilt their balance sheets in response to tighter regulation, including a requirement to match at least 9% of their risk-weighted assets with core regulatory capital, a buffer consisting of equity and equity-like instruments. As shown in the chart below, European institutions now have regulatory capital ratios well above the 9% threshold and above the levels of their US peers, making them relatively safer investments. Another important distinction across the Atlantic is that European banks do not have high levels of unrealised losses in their securities portfolios, nor do they take on significant interest rate risk. This is because they are required to revalue their security portfolios on an ongoing basis and are subject to regular ‘interest rate risk in the banking book’ (IRRBB) stress testing by the regulator. Other than a handful of larger banks, US lenders like SVB are not required to participate in these stress tests.

Source: Bloomberg LLP, J.P. Morgan, 2023

With interest rates languishing at historically low levels for most of the past decade, many banks have been starved of their key source of profit generation, making the decade or so after 2008 a relatively unexciting time to be a bank shareholder. This was particularly true in Europe where banks are more focused on traditional lending, whilst many US banks are geared towards investment banking activities. However, with interest rates having risen significantly, traditional banks in Europe are seeing a tailwind for their profit margins that has not existed for many years. This enhanced profitability comes at a time when their balance sheets have rarely been so robust, with record levels of capital reserves and high levels of regulatory protection in many cases.

This backdrop supports the creditworthiness of European banks as issuers of bonds, including the AT1s mentioned earlier. As we saw with events at Credit Suisse, these are complex instruments which are best accessed through an expert active manager with an understanding of the documentation. Nonetheless, with a low risk of capital loss in the highest quality European institutions, the 8.3% yield offered by AT1s looks attractive. Rising profitability and healthy balance sheets make for compelling return prospects in European bank equities too. Indeed, we have seen several banks recently embark on programmes to return vast sums of excess capital to shareholders. For example, Unicredit is in a position to distribute $5.25bn to shareholders via dividends and share buybacks this year, equivalent to 15% of its market capitalisation. Other European banks such as ING and BBVA have recently declared similar intentions to reward shareholders. These examples give weight to our view that there are potentially outsized returns available within the financial services sector for those willing to look in the right place.

With so much having happened this quarter, the surprise reopening of China’s economy in January feels like a distant memory. Whilst an easing of Covid-19 restrictions was inevitable and many, including us, were envisaging that this might happen sooner than was being telegraphed by officials at the end of last year, the speed of the policy reversal took even the most optimistic investors by surprise. The news sent cyclical commodities like iron ore higher, with Chinese equities also rallying strongly on the news. Since then, Chinese assets have pared some of their gains as it has become clear that three years of strict social restrictions have left psychological and practical constraints on the speed of China’s economic recovery. However, with measures of non-manufacturing activity hitting multi-year highs and passenger transport volumes approaching pre-covid-levels, the outlook for consumer-facing businesses looks particularly constructive. Stimulative monetary policy and a cooling of regulatory interventions from Beijing should also be supportive for the regional market.

A strengthening of Chinese economic activity is one factor that supports our view that inflation is likely to track above central bank targets for longer than the market currently expects. Accordingly, our view is that central banks will keep interest rates at restrictive levels for longer than expected. We continue to believe that the market is being overly optimistic in its current expectation that the Federal Reserve will cut interest rates 5 times before the end of the 2023. With inflation still significantly above central bank targets, particularly in the service sectors that constitute core price measures, we feel that a material easing of monetary policy is a while away yet.

As the world adjusts to higher interest rates, there will inevitably be more bouts of economic indigestion. We retain an element of caution in our stance, reflective of the prevailing uncertainty, but have high conviction in our invested positions. We strongly believe that the new economic environment will continue to produce opportunities for long term investors. Whether it is the tailwind for banks provided by higher interest rates, the cyclical upswing for Chinese companies as the local economy reopens or more structural themes such as the acute shortages in metals critical to the green energy transition, we believe our portfolios are positioned to take advantage.