Foreign currency has competed fiercely with other astounding price moves this year for investors’ attention, significantly inflating or deflating returns on foreign assets for international investors. For investors in the UK, investments denominated in US dollars have benefitted from the US dollar’s 12% appreciation against sterling. Depending on your view, this relationship has either alleviated some of the losses delivered by US equity and bond markets this year or temporarily masked them. If you take the latter view, multi-asset investors running foreign currency exposure, particularly to the US dollar, may be fighting a headwind from here, notwithstanding any positive returns from their underlying investments. We take this opportunity to highlight the importance of currency in a diversified portfolio and explain our approach to foreign exchange markets.

In September, the US Dollar Index, a measure of the dollar’s purchasing power against six major global currencies, hit a 20-year high. This concluded a relentless ascent by the US dollar against virtually all other currencies this year, as aggressive interest rate hikes by the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) created significant demand for its currency. As well as having a central bank willing to raise interest rates relatively quickly and aggressively compared with other central banks, most notably those in Europe and the UK, the US economy has been producing inflation that is less severe than that experienced in most other developed markets. Economic theory dictates that an economy with higher inflation will see its currency depreciate to maintain an economic constant known as ‘purchasing power parity’. This relationship has created a virtuous circle in the US whereby its relatively more benign inflation has kept its currency strong, tempering its future inflation. The inverse has been true for other, non-dollar economies. Together, comparative inflation and interest rate dynamics in the US economy go a long way towards explaining the dollar’s strong performance this year.

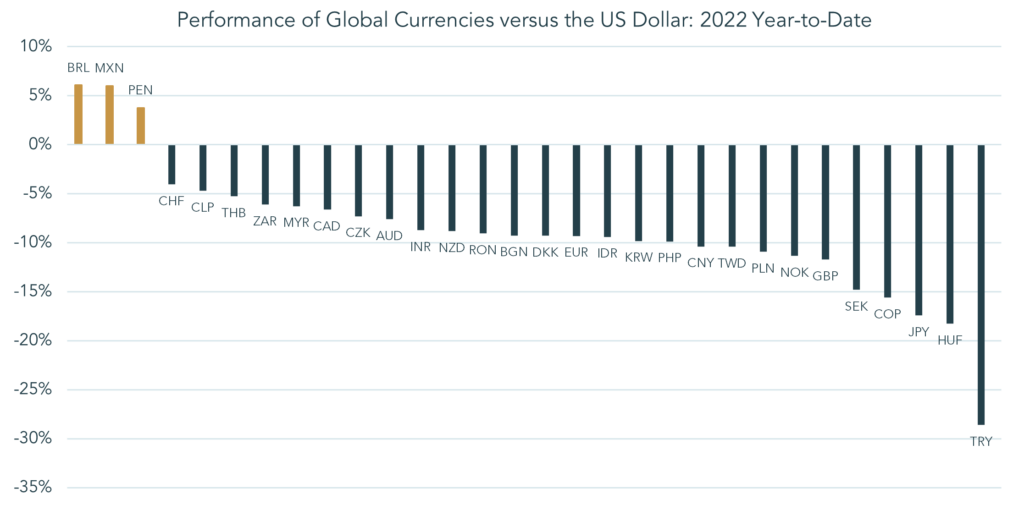

Strong currency performance has not been restricted to the US dollar, however. Certain emerging market central banks chose to raise interest rates fast and early, most notably those in Brazil, Mexico and Peru. Thanks to this, their currencies have appreciated markedly over the year to date, as evidenced by the chart below. In Brazil, a combination of high commodities prices and a proactive central bank that has hiked rates from 2% in early 2021 to nearly 14% today has made the Brazilian real one of the best performing currencies this year. Their economy has fared well over the corresponding period, with inflation on a downward trend since April. On the other end of the spectrum is Turkey, where President Recep Erdoğan has decided not to subscribe to common economic theory and has cut the interest rate in the country in response to rising prices. This has led to rampant inflation of nearly 80% and a devaluation of the Turkish lira (TRY) versus the US dollar, by nearly 30%.

Data as at 30th November 2022 Source: Bloomberg LLP, 2022

The relationships between interest rates, inflation and currency are well established and not unique to the US dollar. What is rarer, however, is the status of the US currency as the reserve currency of the world. With this status comes a perceived safe haven quality, leading investors to hold more of this currency during periods of elevated volatility in financial markets, such as the past year. This intangible characteristic has driven the US dollar higher than economic forces alone might have done, with the currency attracting significant capital flows in the face of adverse market conditions. Looking to the future, one can build a strong case to suggest that this tailwind for the dollar may become a headwind. With the US government having led the international community’s sanctioning of Russian assets denominated in dollars, following similar instances of financial choking in Venezuela and Iran, major world powers with divergent long-term objectives to America may look to re-think the composition of their currency reserves. The significant stockpiles of US dollars held by economies such as China, Russia and Japan may be increasingly supplemented by other assets, as leaders look to insulate themselves from the future wrath of the global ombudsman. A structural decline in the amount of dollars held in reserves could well prove to be a quiet drag on the dollar’s performance in the coming decades.

The yen is another currency often thought to share the US dollar’s safe-haven status. By contrast, capital flows surrounding the Japanese currency have been considerably less favourable this year, leaving the yen as one of this year’s worst performing currencies. Since the early 1990s, Japan’s economy has struggled to generate an inflation rate above zero. The reason for this stagnation is the subject of much academic literature, but some commonly accepted explanations are as follows:

- Workplace culture – negotiating increases in wages carries cultural stigma, preventing price increases from spiralling into higher wages. Labour unions are also more focused on job security than rates of pay.

- Demographic challenges – with 38% of the Japanese population over the age of 60 and birth rates stubbornly low, the country’s aging population is a drag on economic growth, keeping prices at depressed levels.

- Housing oversupply – the Japanese economy still wears the scars of the housing bubble of the 1990s, during which a huge oversupply of property preceded a slump in property prices which depressed the cost of rent for many years afterwards, reducing the impact of housing costs on inflation metrics.

In an attempt to stimulate growth in the economy, the Bank of Japan (BoJ) has been manipulating the country’s money markets through a process called Yield Curve Control since 2016. Through this scheme, the Bank has sought to keep the cost of long-term borrowing at rock-bottom levels in the hope that cheap debt will stimulate growth. A side effect of Yield Curve Control is weakness in the Japanese yen, since low interest rates make the currency unattractive to international fixed income investors. If the BoJ were to abandon Yield Curve Control, the relative attractiveness of the yen to investors would increase. Such a break in policy may well be due, as during the last year the yen has fallen rapidly. The Japanese government has already had to defend its currency from dropping too far, too fast; most notably in October when it spent $43bn of reserves to support the yen, having also spent $20bn buying its own currency in September. These purchases, the first since 1998, are creating tension between the objectives of the BoJ and the government.

With inflation in Japan hitting 40-year highs, there is speculation about the need for a watershed policy change from the BoJ. The central bank should welcome some inflation, as Japanese consumers are now more likely to make purchases in the present, rather than at potentially inflated prices in the future, thus spurring economic growth. Importantly, however, rising prices appear to be filtering into the labour market more meaningfully than they have in recent history. Japanese workers are expected to push for their first serious wage increases in years during the next round of union wage negotiations in Q1 2023. These structural developments in the inflation cycle, not seen since the 1990s, leave the BoJ at a policy crossroads. It can relinquish its grip on interest rates by stopping Yield Curve Control, or it can continue with its loose monetary policy and stimulate growth. The cost of the latter route may be rising inflation and persistent weakness in the Japanese yen. Whilst the ultimate economic effects of the former option are unclear, we believe it is an increasingly probable path for the BoJ, likely to cause a significant rally in the yen if it is taken.

As a rule of thumb, we look to maintain a well-diversified exposure to global currencies within our discretionary portfolios. The starkly contrasting performance of the Japanese yen and the US dollar this year make the benefits of currency diversification particularly intuitive at the moment. However, our desire for this is more strategic than simply hoping losses in one currency will be offset by gains in another during volatile times. Currencies are reflective of macroeconomic forces that are not necessarily visible in other assets, acting as a balancing mechanism for differences in economic conditions between countries. As well as adding another layer of diversification to our investment strategy, a blend of currency exposure allows our portfolios to benefit from these mechanics.

Having said that, we are not afraid to make active currency decisions when presented with what we believe to be a structural mispricing in one of the major currencies to which we have exposure. In these instances, we will make tactical adjustments to our currency positioning in order to benefit from a correction in this pricing. These instances are rare, and our reactions are subtle, but it would be wrong of us to ignore opportunities to add incremental returns to our clients’ portfolios. For example, with the Bank of Japan looking increasingly likely to tighten its monetary policy, we have recently increased our exposure to the yen to benefit from an expected strengthening in the Japanese currency. If recent currency volatility continues, we will no doubt be presented with more opportunities to make tactical adjustments to our currency exposure.

Lincoln Private Investment Office