” You can see the computer age everywhere but in the productivity statistics.” – Robert Solow, Nobel Prize winning economist.

Artificial intelligence has shaped markets in a way that few other forces have, but its importance for investors is often misunderstood. AI is best thought of not as a sector or a short-term growth theme, but as a general-purpose technology, where the economic impact will emerge unevenly across firms, industries and time horizons. Markets, however, can be tempted to price such technologies as if benefits are immediate, persistent and broadly captured by early leaders. This can result in a disconnect between where capital is allocated and where long-term value may ultimately accrue. The investment question is therefore not whether AI will matter, but who captures its potential and at what price.

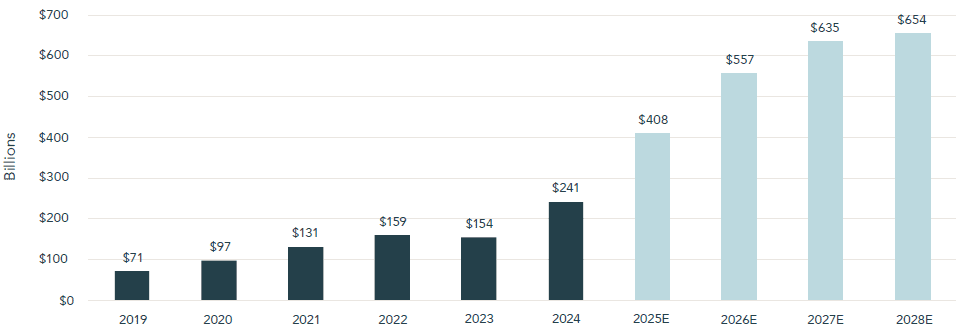

Market confidence in artificial intelligence has risen rapidly since 2022, driven by visible progress in model capability and an acceleration in corporate adoption. This confidence has been reinforced by the scale and transparency of the infrastructure buildout now underway. Hyperscalers and other large corporates have committed vast sums of capital to data centres, advanced chips and energy capacity, as shown in the chart below. This provides investors with tangible evidence that AI is being taken seriously at the highest levels of capital allocation. Equity markets have responded accordingly. Returns have become increasingly concentrated in a narrow group of firms most directly exposed to this spending, elevating their weight within major indices and commanding premium valuations. What matters for investors is that this enthusiasm is no longer tentative or speculative; it is already embedded in balance sheets, capital budgets, and market leadership.

Capital Expenditure from the Major AI Hyperscalers (Alphabet, Amazon, Meta, Microsoft, Oracle)

History suggests that recognising the transformation is easier than capturing the returns. Robert Solow’s remark is a reminder that adoption and monetisation rarely move in step. Railways transformed commerce, yet overbuilding and intense competition compressed returns for investors. The internet rewired the economy, but many early leaders failed, and even durable winners could disappoint when investors started from stretched valuations. The recurring pattern is that once a technology is clearly important, capital and competition arrive quickly, and the surplus often ends up somewhere other than where investors first assume it will concentrate.

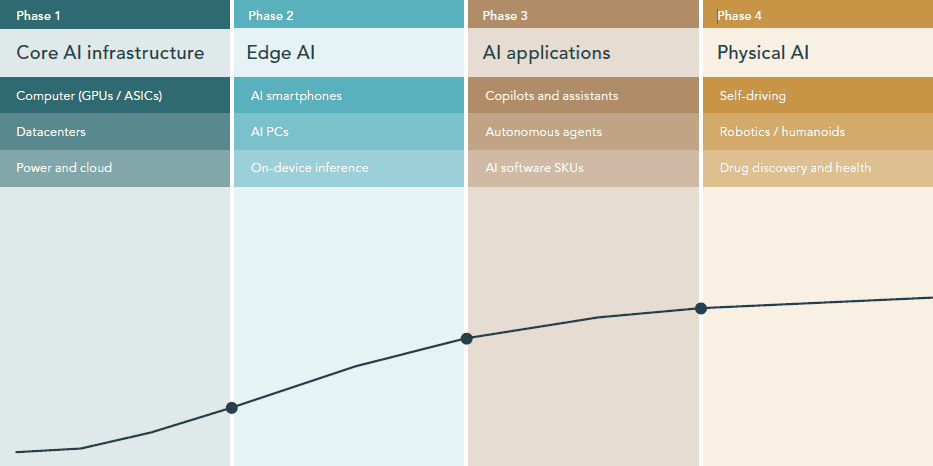

A useful way to frame this is the difference between beneficiaries and compounders, as defined by Coatue Management, a technology investment firm. Early in an adoption cycle, spending concentrates on infrastructure and enabling technologies. Revenue is closely tied to the build out of capacity, progress is visible, and earnings momentum can be strong. These businesses, known as beneficiaries, often lead markets early because their exposure is easy to explain and the numbers move quickly. The pattern broadly follows an S curve of technological adoption: first investment rises as capacity is built, then usage spreads across industries, and only later do productivity gains translate into sustainable profits. In the early phase value tends to accrue to suppliers of computer power, hardware, and tools, while the later phase shifts value towards businesses that embed the technology into workflows and capture recurring economic benefit.

In capital intensive technology cycles, visible demand attracts capital, capital expands supply, and competition forces a greater share of the efficiency gains to be passed to customers rather than retained as margin. Cloud computing illustrates this clearly, as rapid enterprise adoption and falling computing costs benefited customers and the broader economy, while only a narrower group of infrastructure providers consistently captured profits. The technology created enormous economic value and adoption accelerated across industries, but the investment outcomes were uneven because markets initially overestimated how widely profits would accrue.

AI S-curve: phase of adoption and value capture

Some infrastructure providers captured sturdy returns, while many application providers faced pricing pressure and rising competition even as usage grew. The lesson is not that the technology failed, but that investors can still be disappointed if they pay peak certainty prices. Cisco remains a useful reminder that a strategically important winner can still deliver weak long run equity returns from an over optimistic starting valuation. After peaking in March 2000, the shares fell by roughly 85 percent over the following two years and, despite continued revenue growth, took more than a decade to regain their prior high.

Compounders typically emerge later. They use AI to reinforce existing advantages, deepen integration, strengthen pricing power, and improve unit economics. The benefit is less obvious in the early data, and harder to compress into a single narrative, which is precisely why compounders can be underappreciated while attention remains fixed on the most visible beneficiaries. The distinction matters because markets do not wait for the economics to settle. Once a theme becomes consensus, the question shifts from who has exposure to who is defensible, and that can change quickly. Small shifts in perceived moat, bundling risk, or competitive intensity can trigger sharp rotations in leadership well before fundamentals have actually changed.

A clearer example is the recent sell off in many software companies. As new AI tools began to complete tasks that previously required dedicated applications, investors quickly questioned how protected those revenues were, and share prices reacted before earnings changed. The step change in model capability, highlighted by Anthropic’s Claude Opus and the broader shift towards agentic systems, has forced investors to reassess where durable value truly lies. If an AI model can retrieve documents, use tools, query internal systems, and complete multi step tasks to produce a finished work product, then some applications begin to look less like defensible platforms and more like interfaces that can be replicated, bundled, or automated away. Recent developments in legal research, contract review, and compliance workflow software providers illustrate this clearly. Share price declines of roughly 30 percent in companies such as RELX Group, Thomson Reuters and DocuSign highlight how quickly market confidence can shift as investors question whether these businesses are truly defensible or simply well packaged processes.

The point is not that AI will kill traditional software providers, nor that incumbents cannot adapt. It is that in periods of rapid change, perception can move faster than proof. Valuations adjust first, narratives adjust faster, and concentration risk builds before the long run economics are clear. That is exactly why the beneficiaries versus compounders distinction is useful. Beneficiaries tend to look strongest when the story is accelerating, because growth is visible and easy to underwrite at a headline level. Compounders are harder to identify, but they are the businesses with enduring pricing power, deep integration, and the ability to absorb new technology while protecting, or expanding, their profitability.

Taken together, these dynamics argue for discipline rather than indiscriminate exposure. Our portfolio positioning reflects a clear distinction between believing in the importance of artificial intelligence and paying any price for participation. As the theme has moved rapidly from emerging to widely accepted, valuation has become a more important determinant of future returns. In parts of the market where expectations already assume rapid adoption, sustained pricing power, and near flawless execution, the margin for error is small. Accordingly, we are willing to underweight richly priced segments even where we share conviction in the long term relevance of the technology. This is not a judgement on the quality of the businesses involved, but a recognition that strong companies can still be poor investments when future outcomes are heavily discounted. Selectivity matters most when consensus is strongest.

We therefore place greater emphasis on the “picks and shovels” of the AI build out. Rather than competing at the front end where products and interfaces can change quickly, we prefer businesses that supply the infrastructure, components, and specialist equipment that enable adoption across the economy. This includes select Asian and emerging market technology leaders at critical points in the global semiconductor supply chain, where AI demand provides a tailwind rather than acting as the sole anchor for valuation. Recent performance illustrates the point, with companies such as TSMC, SK Hynix, and Samsung Electronics having delivered strong share price gains as demand for advanced chips and high bandwidth memory has accelerated with AI adoption. The appeal is a more balanced risk reward; exposure to AI growth without relying on any single application emerging as the winner.

Artificial intelligence represents a genuine technological shift, but successful investing requires more than recognising change. Our approach is to remain exposed to the growth of the technology while avoiding areas where valuations already assume flawless outcomes. We favour the businesses that capture the economics of adoption, not just those most closely associated with it.

Lincoln Private Investment Office.

This document has been prepared and distributed for information by Lincoln Private Investment Office LLP (“LPIO”) and is a marketing communication. LPIO is authorised and regulated by the Financial Conduct Authority. The information in this document does not constitute an offer by LPIO to enter into a contract/ agreement, nor is it a solicitation to buy or sell any investment. Nothing in this document should be deemed to constitute the provision of financial, investment or other professional advice in any way