” If we lost the dollar as the world currency… that would be the equivalent of losing a war.” – Donald Trump

The US dollar (USD) has long stood as the dominant reserve currency of the world, underpinning international trade, financial markets and central bank reserves. As of early 2025, roughly 58% of global foreign exchange reserves remain dollar-denominated. Yet, a confluence of macroeconomic, geopolitical, and structural shifts suggests that this dominance may be under growing threat. In this note, we examine the forces currently pressuring the dollar and highlight the asset classes best positioned to perform in an environment such as this.

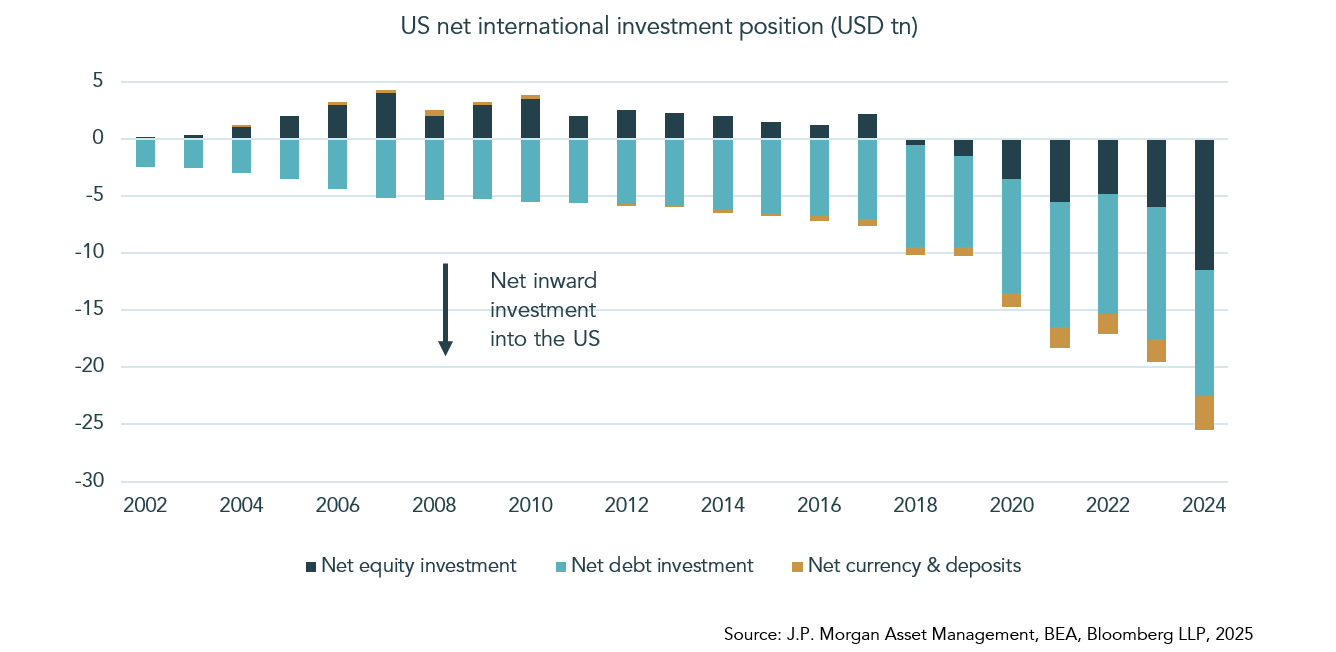

Over the past decade, the US enjoyed a virtuous feedback loop: a strong economy and positive interest rate differentials attracted foreign capital, which boosted the dollar. In turn, this elevated US equity returns for global investors, reinforcing capital inflows. These inflows fuelled domestic consumption and investment, further driving growth and equity markets and by extension, the dollar. All of this demand for US assets, and specifically US government bonds, known as Treasuries, helped bring borrowing costs down as foreigners bought up supply. Cheaper money made it easier for the government to finance its budget deficit and for companies to raise capital and consumers to get credit. The chart below shows just how extreme the investment flows into the US have been since the early 2000s, with a net $25tn of foreign capital making its way into US debt, equity and currency.

This cycle has provided US consumers with buying power, allowing them to import increasing quantities of goods cheaply due to the dollar’s strength. Conversely, the strong dollar has reduced the competitiveness of American-made goods in the international market, hollowing-out domestic US production. Manufacturing employment has plummeted — from 24% of the workforce in 1974 to just 8% by the end of 2024. As production shifted offshore, the trade deficit widened, leaving the US increasingly reliant on imports and foreign capital. President Trump has sought to reverse this dynamic through tariffs and protectionist trade policies. His ambition of a weaker dollar that revives US manufacturing, shrinks the trade deficit, and appeals to his blue-collar political base has begun to play out, but the approach has come at a cost.

The tariffs meant to boost domestic industry in practice, have instead generated uncertainty. Capital expenditure intentions — as measured by regional Federal Reserve surveys — have dropped to levels last seen during the 2020 pandemic. Many companies suspended forward guidance in Q1, and bond markets, which rely on confidence to maintain stability, have wobbled on fears of stagflation (stagnating growth, high inflation and high unemployment) as well as policy volatility. The S&P 500’s near 19% peak-to-trough drawdown prompted a policy retreat: most new reciprocal tariffs were paused within a week, though a baseline of 10% remained. Tariffs affecting trade with China took longer, but were also reduced to c.30% when the impact of an effective trade embargo became clear.

This retreat may have come too late to stem the erosion of investor confidence. Markets are questioning the credibility of US policymaking and, by extension, the dollar’s reliability as a safe currency. A more unpredictable and insular America risks reversing the capital flows that underpin the dollar’s strength. Already this year, the trade-weighted dollar index has declined more than 8%. Aside from trade, fiscal policy is driving some of the dollar’s recent weakness. The US federal deficit is projected to average over 6% of GDP throughout the coming decade, the highest shortfall outside of a recession, despite the economy and employment being in reasonably good shape. Regardless of this alarming trajectory, the government continues to champion expansive fiscal measures. The so-called “One Big Beautiful Bill Act,” which seeks to extend unfunded tax cuts, would push the deficit even higher. Meanwhile, rising interest payments are consuming an increasing share of federal revenues. The US now spends more on interest payments than it does on defense.

The impact of this has been evident in government bond yields. Long-dated bond yields have risen year to date, signifying investor uncertainty over unfettered spending. But while higher yields usually mean a strong dollar, here too has discomfort over fiscal largesse had a negative impact, instead causing the currency to fall. To quote Barclays’ Marek Raczko: ‘’This suggests that the market is challenging the US’s safe-haven status and trading the dollar in line with US policy concerns.”

Historically, foreign buyers — notably China and Japan — have absorbed a large share of US Treasury issuance, ensuring dollar demand. But this dynamic is changing. Chinese holdings of Treasuries have declined nearly 40% over the past decade and Japan’s holdings have flatlined. If confidence in the US regime falls further, the latent foreign demand for US Treasuries may reverse, pushing borrowing costs even higher in the United States and reducing demand for the dollar. The potential for a bond market reckoning, where yields move drastically higher becomes more of a possibility without this source of demand.

Beyond fiscal concerns, geopolitical shifts are accelerating efforts to reduce dollar dependence. Countries like China and Russia have spearheaded initiatives to conduct more trade in local currencies with bilateral agreements emerging across the Global South. The share of Russia-China trade settled in the yuan or rouble has surged from 3% to over 90% in just over a decade. At the 2024 BRICS summit, members even floated the idea of a shared cross-border payments system to bypass the dollar. While implementation remains distant, the direction of travel is clear. Many countries are motivated by a desire to insulate themselves from US financial leverage and sanctions.

Central banks are also responding. Net gold purchases, particularly by China, are rising sharply as countries seek diversification from dollar-denominated reserves. In each of the past three years, global central bank purchases have been more than double the average over the previous decade.

Individually, these trends may appear incremental. Taken together, they represent a meaningful challenge to the dollar’s supremacy. So how should investors respond?

Historically, commodities are the most obvious beneficiaries of dollar weakness. As the dollar falls, commodities become cheaper in other currencies, driving demand. Between 2001 and 2008, the dollar fell 40%, while oil surged from $25 to $140 per barrel. Gold and copper saw similar gains.

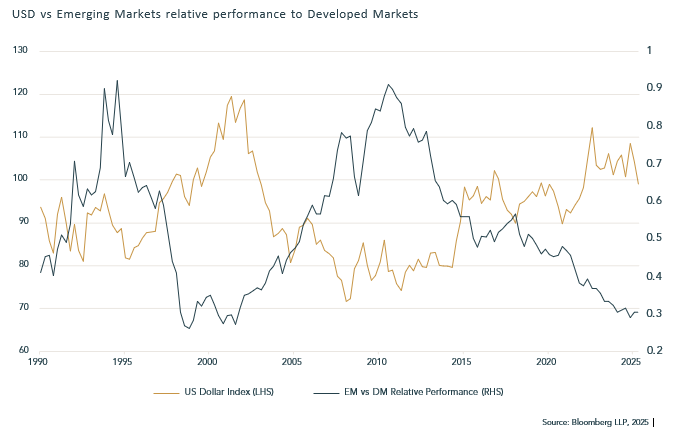

Emerging markets also benefit. As the below chart illustrates, their equity market performance versus developed markets is deeply influenced by the dollar, with gains inversely correlated to the USD. Emerging markets’ large dollar-denominated debts become easier to service as local currencies appreciate, which frees up cash flow for growth. These economies — often commodity-rich and demographically advantaged — attract renewed capital flows as risks of default decrease. Equity markets rally in sympathy, as happened in the early 2000s. This represents somewhat of a virtuous cycle of its own, with local currencies usually stabilising and attracting further investment. Add in the fact that valuations compared to developed markets start at levels not seen since the early 2000s and it is clear why we are excited about the opportunities here.

Even developed markets can outperform. In 2025 so far, German equities are up over 30% in USD terms, while the S&P 500 has remained broadly flat. As foreign currencies strengthen, US investors gain additional returns from exchange rate movements — a powerful incentive to diversify internationally. With marginal capital flows diverted to other markets, the dollar’s decline becomes a windfall for the rest of the world.

Currency markets are notoriously difficult to predict over the short term. However, when structural imbalances appear to be building, and when these are reflected in long-term valuation and positioning, we believe it is appropriate to lean into the themes that may unfold over longer time periods. At Lincoln, our portfolios are well-diversified across currencies and asset classes, with positions in the Japanese yen and emerging market local currencies complemented by a diversified regional equity exposure. Our exposure to physical gold and the broader commodity complex provides a hedge against dollar devaluation and inflation.

The era of dollar dominance may not end tomorrow. But its gradual erosion, driven by fiscal excess, shifting geopolitics, and a multipolar financial world, may already be underway. It should be noted, it is simpler for the US dollar to fall when the explicit aim of the President and his policies is exactly that. A lower dollar would serve to close Trump’s despised trade deficit and bring home manufacturing jobs. Whether this will increase GDP in the long run remains to be seen. The transition will not happen overnight, but rather over many years. The US risks undermining its own currency in the short term by walking a tightrope between deliberate devaluation and structural collapse. These dynamics would suggest it pays to remain well diversified in this time.

Lincoln Private Investment Office