“I prefer an uncomfortable truth to a comfortable lie.” Javier Milei

The final quarter of 2024 lived up to its action-packed billing. Economic indicators in the UK had been showing depressed levels of activity as the country waited to hear from a Labour chancellor for the first time in 14 years. The hiatus contributed to the Office of National Statistics’ revision of growth in the third quarter down from 0.1% to zero, with the Bank of England forecasting no growth in the fourth quarter either. The market appeared to take the Autumn Budget broadly in its stride, albeit with some disappointment that the government had not taken the opportunity to lay out a clear plan for growth. Whatever one’s thoughts on its contents, with the Budget behind us, businesses and individuals at least have more clarity, which markets tend to prefer.

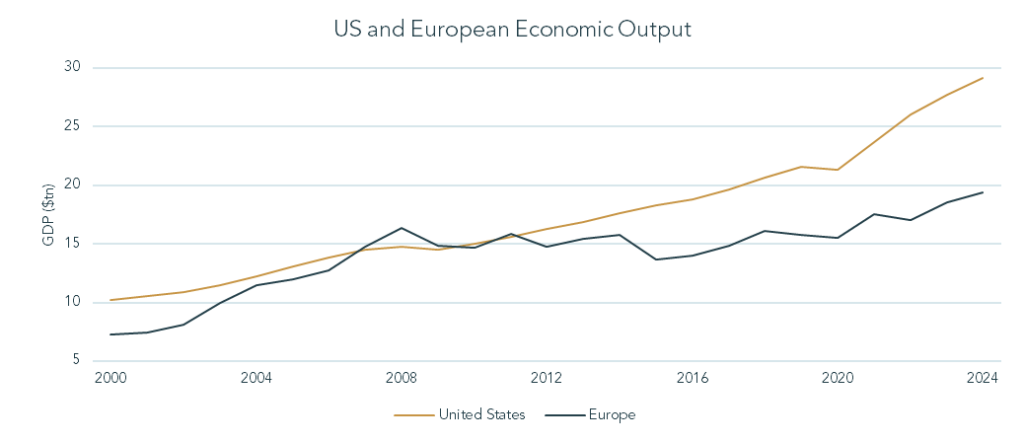

Nowhere was this more evident than in the United States, where victory for Donald Trump in the presidential election saw the dollar and US equities strengthen. The prospect of a pro-business, pro-America Trump regime has re-ignited the idea of US exceptionalism in the minds of investors. The term is often used in reference to the premium valuation of US assets, owing to the perceived superior potential of the US economy compared to its peers. As a developed economy underpinned by democratic institutions and Western values, Europe is a natural comparison to the United States. Since the Global Financial Crisis of 2008, the US economy has proven an ability to grow at a consistently higher rate than Europe, as shown below. This has allowed many of its financial assets to maintain a premium valuation.

Source: IMF, 2024

The initial market reaction to Trump’s victory suggests that he is seen as supportive of this trend continuing. We discussed the potential implications of a Trump presidency in our Market View piece in November, so please refer to this for a fuller take on the matter. In short, it is expected that Trump will pursue a pro-growth agenda, fuelled by a wider fiscal deficit. Alongside deregulation of industries like energy and healthcare, we expect to see tax cuts for both individuals and corporations. Whilst the imposition of tariffs would raise a modest amount of tax revenue, as would cutting subsidies for green energy, without meaningful commitments to cut back spending we will likely see the budget deficit widening over the coming years. As the probability of a Trump win increased, bond markets moved to price the higher levels of borrowing that the US will require to fund itself, in addition to higher inflation expectations as a result of his policies.

One relatively unquantified factor, which may partly mitigate this deteriorating US fiscal position, is the proposed scaling back of government agencies, particularly the size of the federal workforce. Responsibility for the rightsizing of America’s public sector has been handed to the Department for Government Efficiency, known as DOGE, which will be spearheaded by businessmen Elon Musk and Vivek Ramaswamy. It has been suggested that the vision has been partly inspired by the success to date of Javier Milei, the radical libertarian President of Argentina.

Argentina has been the best performing stock market in 2024, whilst its government bonds have also generated substantial gains for investors. Among Milei’s inflation-busting policies was a halving of the number of government ministries, a policy which has garnered a remarkable amount of public ‘buy-in’, despite its adverse short-term impact on unemployment. The Trump administration is unlikely to have the same degree of popular support for mass redundancies or, importantly, the same control over staff in federal agencies. Nonetheless, it is interesting to see Trump pursuing a concept which very few leaders of developed economies have as yet been bold enough to follow through on.

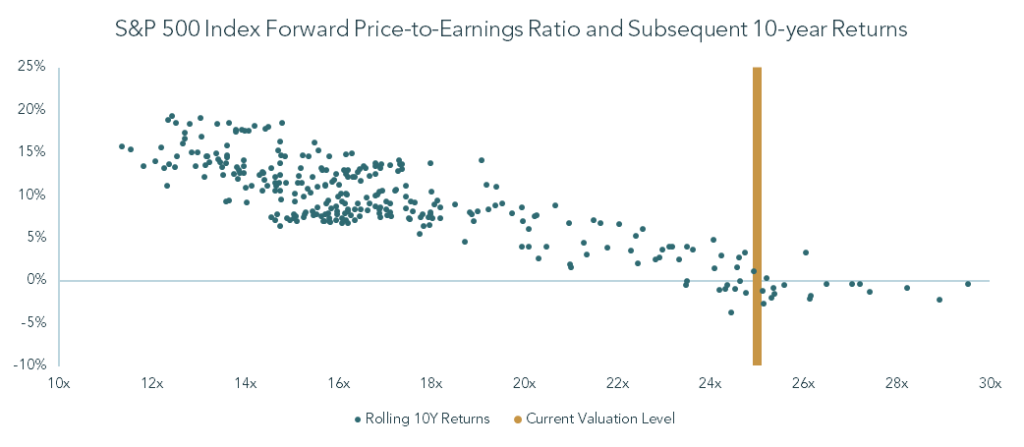

Whilst the economic and political backdrop in the US looks conducive to business and investment, investors must also consider what is reflected in asset prices. In US equities, expectations are very high when looking at the index as a whole. The S&P 500 Index trades on a 25x multiple of prospective earnings, a historically expensive level. So, whilst the outlook is attractive for listed US companies, they are very much priced to reflect this. Indeed, subsequent returns from times when expectations have been this high historically have generally been underwhelming. The historic relationship between the valuation of the S&P 500, as measured by the forward price-to-earnings ratio, and returns over the subsequent 10 years is presented below.

Source: Bloomberg LLP, 2024, monthly data since 1990

As always when considering macro data, this graph misses some considerable nuance. An important detail, in our view, is the current concentration in the S&P 500 Index, with the top 10 companies accounting for nearly 40% of its market capitalisation. These companies are also some of its most expensively valued constituents, meaning that a small number of companies are skewing the valuation of the index overall. For this reason, we have positioned our portfolios to participate in a broadening of returns to companies outside of this small group. We believe that US economic strength will have wide-ranging benefits which are not fully priced into all listed American equities. For example, US smaller companies are valued in the middle of their historical valuation range, whilst the valuations of large US companies are currently in the top decile of their range. Positioning to capture this valuation disparity also has the inherent benefits of diversification, spreading our exposure across a better mix of companies than is achievable by simply tracking the US index.

If US equities are in favour, then Europe is very much out. Both its economic data and investor sentiment are weak, with European equities trading on a price-to-earnings discount of 40% to their US peers and economists expecting growth of just 1.1% in 2025. With Chinese competition threatening some of Europe’s major industries and two of its largest economies, France and Germany, currently lacking stable governments, it is easy to buy into this gloomy consensus, especially when you throw in the risk of shocks from the Russia-Ukraine War or US tariffs. However, much as one ought to tread carefully when expectations are lofty, it pays to remain open to investing in unpopular parts of the market. Abundant negativity leaves a low bar for surprises to the upside.

For example, if President-elect Trump proves successful in his bold assertion that he will broker a peace deal between Russia and Ukraine, sentiment in Europe could rebound sharply, particularly if it led to higher growth and lower energy prices. Of course, this outcome remains unlikely, but the market appears to ascribe it a near-zero probability. With unfathomably high numbers of Russian casualties, sanctions gradually biting its economy and Russia’s influence dented by the ousting of Bashar-Al-Assad by rebels in Syria, a probability of zero does not feel right.

The European Central Bank (ECB) may provide another source of reprieve for the region, having already cut its key interest rate to 3% from a peak of 4%. If the ECB were to move more decisively to support growth, further interest rate cuts could help stimulate ailing sectors such as real estate and construction, as well as freeing governments to allocate more capital to productive ends instead of servicing debt interest. Germany could further benefit from a relaxation of its fiscal ‘debt brake’ which has prevented it from loosening its fiscal policy to the degree of its developed market peers. Whilst Friedrich Merz, the favourite to become Germany’s next chancellor, has not committed to this change ahead of the election in February 2025, it is supported by many senior figures in Germany and may be the only way for him to deliver on his promises to increase defence spending and cut taxes. As with any peace deal in Ukraine, these are not our central assumptions, but they are additional reasons we remain comfortable maintaining material exposure to the innovation and attractive valuations on offer in European equities.

Although less well-covered by the mainstream media, Japan has also produced some political uncertainty recently, which we think is worth commenting on. In September, Prime Minster Shigeru Ishiba replaced Fumio Kishida, who had been hampered by dismal opinion poll ratings in the aftermath of what has become known as the ‘Slush Fund Scandal’. Kishida was ultimately forced to resign after it emerged that his party (the LDP) had broken election and campaign finance laws. On arrival in office, Ishiba sought to re-affirm his party’s mandate to govern by calling a snap election in October. Instead, voters punished the LDP, leaving Japanese politics in a state of flux with no party winning a clear majority. However, this political noise is unlikely to derail the key structural themes in Japan’s investment landscape.

With inflation and wage growth indicators looking strong, we think the Bank of Japan will have to raise interest rates in due course, which should be beneficial for the Japanese yen, especially if this coincides with an easing of interest rates in the US. These upwards price pressures are indicative of healthy activity in the economy which, combined with attractive valuations, are continuing to attract both public and private equity investors to Japan. Corporate activity ramped up in 2024, with several major events including the privatisation of Toshiba by a consortium of institutional investors and the largest ever foreign takeover bid received by convenience store operator 7-Eleven. With corporate governance and culture in Japan continuing to evolve in a more shareholder-friendly direction, the outlook for Japanese equities is compelling.

Looking into 2025, it is easy to focus on areas of political risk, particularly as a transition of power in the US is expected to bring with it a more confrontational style of international relations. Partly for this reason, we deliberately strive for geographic diversification in our portfolios, as well as allocating to alternative assets. However, 2024 was also billed as a year of potential political turmoil, with numerous major elections across the world. Ultimately, equity markets, particularly in the US, shrugged this off to perform handsomely. This serves as a useful reminder that headlines do not drive investment returns in the long run. For those willing to look beyond the noise, there is plenty of scope to seize opportunities that can pay dividends irrespective of the headlines of the day.