In November 2020, the global market value of negative-yielding bonds, which require their holders to pay for the privilege of owning them, reached 18 trillion US dollars. By January 2023, following an aggressive interest rate hiking cycle by central banks, that figure had reduced to zero. These rate hikes, required because of inflationary price pressures, broke the downward trend of interest rates over the past 40 years. Now, with global bond markets nearing a third year in a row of losses, and government bond yields near 15-year highs, the era of zero or even negative interest rates is fast becoming a distant memory.

For us at Lincoln, fixed income and especially government bonds had become uninvestable as interest rates fell toward zero. Whilst our long-term asset allocation will always feature this asset class, the lack of value we saw ensured that we found alternative ways to implement this allocation. We preferred to invest in managers that were uncorrelated with their wider sector, but who had the same volatility profile that fixed income traditionally offers.

Over the last two years central banks have raised rates in order to slow their economies and thereby reduce inflation, reversing the low interest rate environment markets have enjoyed for so long. Alongside this, we have seen a withdrawal of direct monetary support. For most of the last 15 years, the Federal Reserve (the Fed) has been the marginal buyer of US government debt, helping to force down fixed income yields to historic lows with its constant bid for bonds. As the Fed wound down this process, known as quantitative easing, investors sold government bonds aggressively as they were faced with the prospect of a negative real return (low yields and high inflation). With the Fed raising interest rates from near zero to over five percent and no longer buying government debt, bond prices fell materially, and yields jumped higher. To us, this repricing has made bonds investable again. It is hard for an investor to ignore a ‘risk-free’ asset such as the US 10 Year Treasury when it offers the same yield as the S&P500 index, but without the additional equity risk. For the first time since 2007 you can now achieve c.4.50% in a basket of US government bonds, making them look attractive on both a standalone and relative basis, while also providing diversification benefits to a blended portfolio.

Nevertheless, as an investor one must look at the whole context. Whilst we believe UK interest rates are likely to have peaked and therefore downside risk to gilts (UK government bonds) is limited, we do see the potential for further losses to US Treasuries. Our rationale for this begins with the fact that UK mortgages tend to be floating rate or fixed rate for up to 5 years, rather than being fixed for a very long period as in the US, where they are typically fixed for 30 years. Hence, the increased cost of mortgage financing works its way through to the UK consumer much faster thanks to their shorter financing terms, reducing the need for interest rates to go higher to slow the economy. In the US, however, where mortgages do not need to be refinanced for a much longer period, the American consumer only faces the impact of rate rises on their other, usually smaller, loans. Therefore, interest rates may be required to remain restrictive for longer to slow the US consumer’s spending in the same way. Further to this, significant bond issuance is required to fund a record US government deficit of approximately 8% in the coming years, with the excess supply expected to result in weakness for US government bonds. Noticeable too, is that the largest foreign owners of US Treasuries, Japan and China, continue to sell their holdings and repatriate capital onshore.

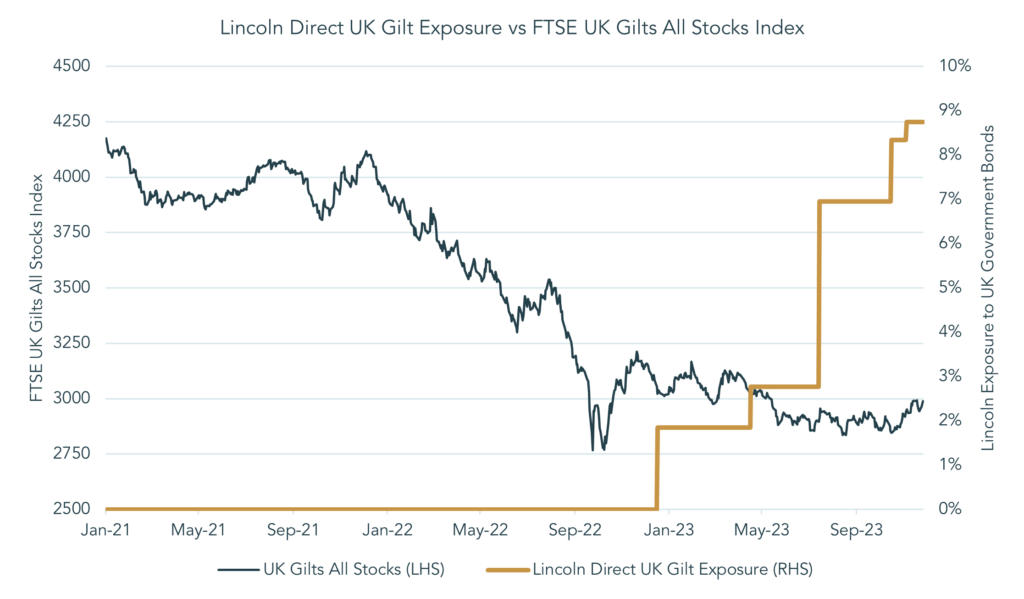

As a direct consequence, over the past year we have added UK government bonds to our portfolios at opportune moments, edging in slowly at first and increasing in conviction over time. The chart below shows the exposure to UK government bonds in our core portfolio and the UK Government Bond Index (which is inversely related to bond yields). The core portfolio, a portfolio that reflects our average client, currently holds 8.75% of its portfolio in standalone UK gilts with further exposure within some of our other funds. In addition to the attractive nominal returns offered by these gilts, they provide an additional benefit to UK taxpayers through a tax exemption on capital appreciation.

Source: Bloomberg LLP, 2023

In November 2020, the global market value of negative-yielding bonds, which require their holders to pay for the privilege of owning them, reached 18 trillion US dollars. By January 2023, following an aggressive interest rate hiking cycle by central banks, that figure had reduced to zero. These rate hikes, required because of inflationary price pressures, broke the downward trend of interest rates over the past 40 years. Now, with global bond markets nearing a third year in a row of losses, and government bond yields near 15-year highs, the era of zero or even negative interest rates is fast becoming a distant memory.

For us at Lincoln, fixed income and especially government bonds had become uninvestable as interest rates fell toward zero. Whilst our long-term asset allocation will always feature this asset class, the lack of value we saw ensured that we found alternative ways to implement this allocation. We preferred to invest in managers that were uncorrelated with their wider sector, but who had the same volatility profile that fixed income traditionally offers.

Over the last two years central banks have raised rates in order to slow their economies and thereby reduce inflation, reversing the low interest rate environment markets have enjoyed for so long. Alongside this, we have seen a withdrawal of direct monetary support. For most of the last 15 years, the Federal Reserve (the Fed) has been the marginal buyer of US government debt, helping to force down fixed income yields to historic lows with its constant bid for bonds. As the Fed wound down this process, known as quantitative easing, investors sold government bonds aggressively as they were faced with the prospect of a negative real return (low yields and high inflation). With the Fed raising interest rates from near zero to over five percent and no longer buying government debt, bond prices fell materially, and yields jumped higher. To us, this repricing has made bonds investable again. It is hard for an investor to ignore a ‘risk-free’ asset such as the US 10 Year Treasury when it offers the same yield as the S&P500 index, but without the additional equity risk. For the first time since 2007 you can now achieve c.4.50% in a basket of US government bonds, making them look attractive on both a standalone and relative basis, while also providing diversification benefits to a blended portfolio.

Nevertheless, as an investor one must look at the whole context. Whilst we believe UK interest rates are likely to have peaked and therefore downside risk to gilts (UK government bonds) is limited, we do see the potential for further losses to US Treasuries. Our rationale for this begins with the fact that UK mortgages tend to be floating rate or fixed rate for up to 5 years, rather than being fixed for a very long period as in the US, where they are typically fixed for 30 years. Hence, the increased cost of mortgage financing works its way through to the UK consumer much faster thanks to their shorter financing terms, reducing the need for interest rates to go higher to slow the economy. In the US, however, where mortgages do not need to be refinanced for a much longer period, the American consumer only faces the impact of rate rises on their other, usually smaller, loans. Therefore, interest rates may be required to remain restrictive for longer to slow the US consumer’s spending in the same way. Further to this, significant bond issuance is required to fund a record US government deficit of approximately 8% in the coming years, with the excess supply expected to result in weakness for US government bonds. Noticeable too, is that the largest foreign owners of US Treasuries, Japan and China, continue to sell their holdings and repatriate capital onshore.

As a direct consequence, over the past year we have added UK government bonds to our portfolios at opportune moments, edging in slowly at first and increasing in conviction over time. The chart below shows the exposure to UK government bonds in our core portfolio and the UK Government Bond Index (which is inversely related to bond yields). The core portfolio, a portfolio that reflects our average client, currently holds 8.75% of its portfolio in standalone UK gilts with further exposure within some of our other funds. In addition to the attractive nominal returns offered by these gilts, they provide an additional benefit to UK taxpayers through a tax exemption on capital appreciation.

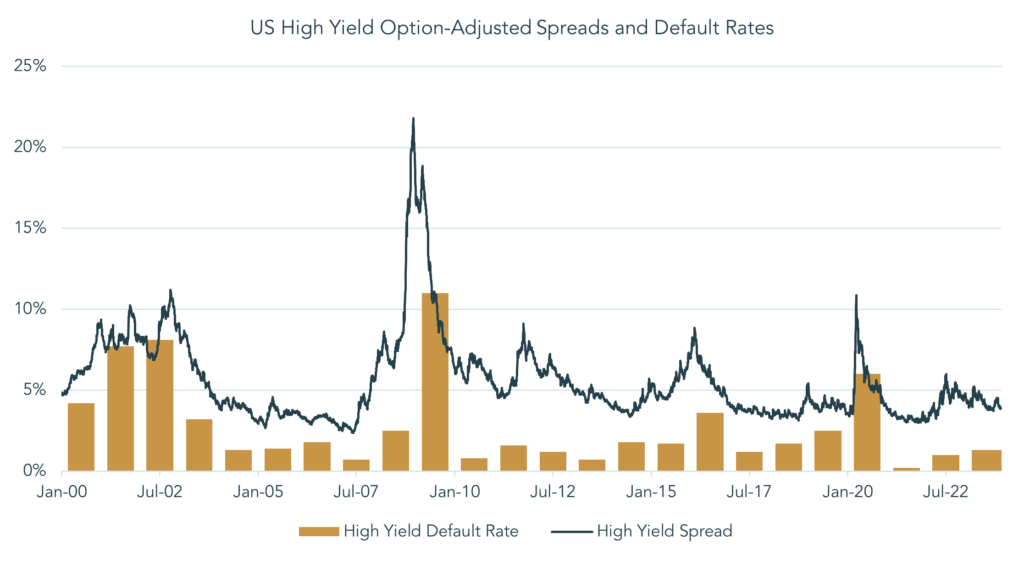

Source: JPMorgan Asset Management, 2023

To look for signs of corporate distress, our attention will be focused on indices like the Russell 2000, where over 40% of companies are unprofitable. When interest rates were low these businesses were capable of surviving on cheap credit, but with the price of money anticipated to remain high for some time, we expect to see some of these companies collapse as their debt load becomes unsustainable. This form of washing out, or ‘creative destruction’ to quote Joseph Schumpeter, helps markets stay healthy. The rise of zombie companies, those that only make enough to service their debt rather than pay it off, has been a direct consequence of the low interest rate environment. Freeing up capital from these companies and reallocating it to those that provide a better return on capital should release a wave of productivity in firms that are more deserving of investor funding. As this process occurs, we should see the spreads on offer increase in the high yield asset class, at which point the Lincoln portfolio is likely to enter more traditional positions within the space.

In short, whilst there are certainly some attractive opportunities out there, we believe the majority of value at this time is to be found within the government bonds asset class. For the first time in a long time, government bonds are offering both a compelling yield and diversification benefits for a portfolio. However, as we move further along the risk spectrum of traditional fixed income assets, we see decreasing value, with corporate debt failing to offer yield commensurate to the additional risk taken. At Lincoln, we believe risk should only be taken when the reward on offer is adequate and are therefore happy to wait in the wings by holding unconventional fixed income funds until such an opportunity arises.

Lincoln Private Investment Office