“Inflation, like the genie in the lamp, is very difficult to control when it is released.”

Iván Martín, Magallanes

We are leaving behind the worst quarter for global equities and bonds in aggregate since 1990. With inflation remaining stubbornly high, central banks have sought to regain credibility by delivering substantial interest rate hikes, most notably the US Federal Reserve (the Fed) which raised interest rates by 0.75% in June. This environment has presented a headache for proponents of traditional portfolio construction, as both conventional bonds and mainstream equity indices suffered heavy losses. A regime of rising interest rates necessitates, in our view, a continuation of our alternative stance in fixed income markets and our selective approach to equities, as we believe the current macroeconomic dynamics will persist for some time yet. In what follows, we explain recent market gyrations and our approach to navigating them.

The UK economy generated year-on-year inflation rises of 9.0% and 9.1% in April and May respectively. In Europe and the US, inflation has been similarly elevated. The size of these inflation numbers can, in part, be attributed to factors that are more one-off in nature. For example, the war in Ukraine has caused a spike in energy prices as a result of sanctions on Russian oil and gas and has also caused shortages in agricultural commodities, which have had a knock-on effect on food prices. To the extent that the war wages on, the prices of these commodities will remain elevated but are unlikely to create spiralling inflation. There is also little that central banks can do to relieve these pressures which are supply-side in nature. Instead, major central banks are increasingly focused on the more structural components of inflation, such as housing costs, which can create inflation that is more self-perpetuating and therefore more problematic for the economy. These are factors over which central banks can exert a greater degree of influence with interest rate increases. Wages are also an important metric to watch, since putting more money in consumers’ pockets can fuel further price increases by vendors.

Alongside inflation-targeting interest rate rises, we have also seen the withdrawal of direct monetary support. For most of the last 15 years, the Fed has been the marginal buyer of US government debt, crushing fixed income yields to historic lows in 2020 with its constant bid for bonds. As the Fed wound down this process, known as quantitative easing, investors sold government bonds aggressively as they were faced with the prospect of a negative real return (low yields and high inflation). With the Fed raising interest rates and no longer acting as the marginal buyer of fixed income, bond prices fell materially, and yields jumped higher. The dynamics of higher interest rates and a withdrawal of monetary support have also been seen elsewhere, notably in Europe and the UK. As a result, the Bloomberg Global Bond Index posted a loss of 8% in Q2, taking year-to-date losses to a staggering 14%.

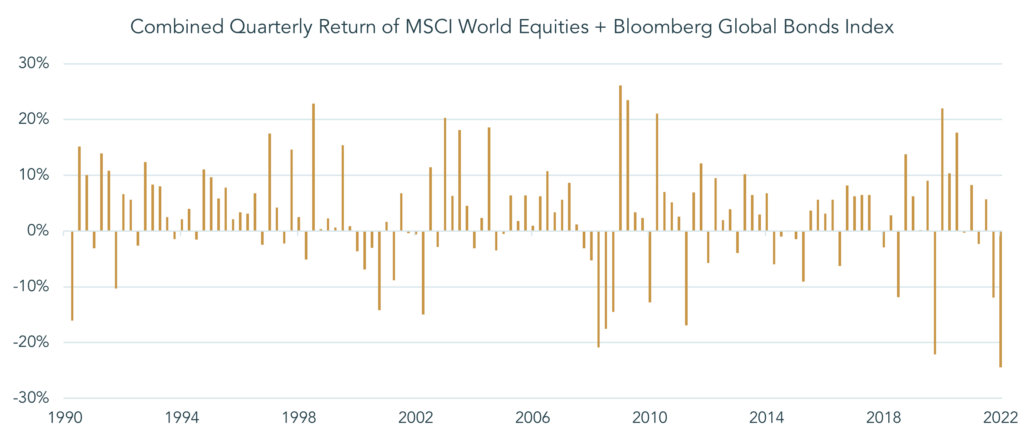

Rising yields affect the valuation of any asset that derives its value from the discounting of future cashflows to a present-day value. Nearly all equities were adversely impacted by this relationship to some degree last quarter, but asset-light sectors such as technology, where much of the value lies in future cashflows, were among the poorest performers. Given the significant proportion of major equity markets accounted for by the technology sector, for example the S&P 500 is 26% technology, investment managers allocating in accordance with market capitalisation have suffered significant losses in their equity portfolios. The pain has been widespread, not least because investing by market capitalisation is typical of passive investment strategies such as ETFs, which have attracted significant capital inflows in recent years. The chart below illustrates the magnitude of the combined losses in bonds and equities this quarter, the largest for 30 years.

Source: Bloomberg LLP, 2022

Despite significant market moves, underlying corporate earnings are yet to move by any material margin. However, concerns about a recession are at the forefront of investors’ conscience. It is easy to see why, with borrowing costs set to increase at a time when consumers are facing a so-called ‘cost of living crisis’ as a result of recent inflation. Naturally, a recession would have a negative impact on the earnings of many companies, which has the potential to drag equities lower still. That being said, equity markets typically anticipate economic downturns. Historically, movements in global equity markets six weeks prior provide a strong indication of the direction of company earnings. If this relationship continues to hold, then some reduction in earnings in the coming months has already been factored in by the market. With recession risk well-flagged, the important thing to get to grips with is the nature of the recession that appears increasingly likely in the next 12 months.

In our view, the severity of the next recession will depend greatly on two things: energy and labour markets. Taking energy first, Europe has been at the epicentre of the recent spike in power prices, with benchmark European gas prices rising to all-time highs shortly after the end of June. Being a neighbour to Russia, it has borne the brunt of Russian gas supply cuts in retaliation to Western sanctions. The US has attempted to step in with increased shipments of liquified natural gas (transported in tankers), but there are logistical constraints on this form of supply compared to pipeline gas from Russia. The reality is that the cost of heating homes and powering businesses in Europe will be considerably higher this winter, which will put pressure on consumer wallets and corporate profits. Elevated oil prices will have a similar impact, ramping up the cost of transport for both individuals and companies. As with gas, there are potential mitigants to high oil prices in the form of increased supply from elsewhere, most notably the Middle East, the US and South America. The degree of assistance these producers can offer is a complex political equation but could be meaningful to economies worldwide.

Regarding labour markets, there are competing forces at play. The Fed has explicitly stated that interest rates will continue to rise until inflation comes down to the Bank’s 2% target. This would suggest that, rather than relaxing monetary policy in response to a recession next year, as is currently priced into bond markets, central banks will continue to raise interest rates despite the slowing effect this may have on growth. Evidence from the past five Federal Reserve hiking cycles supports this assumption, with the Fed in each case only ceasing to hike interest rates once US unemployment rose materially from its recent trend. With wage growth showing signs of picking up and employment at a healthy level, additional inflationary pressure from consumers seems more likely in the near term than a faltering labour market, which should keep the Fed focused on rate increases for the time being. Whilst higher rates will present an economic headwind, rising wages should offer consumers some protection from rising living costs, which may mitigate some of the effects that recessions of the past have had, for example 2008.

Ultimately, it is too early to tell exactly by how much the economy will slow and how long it will take to recover thereafter. However, one can say with some certainty that the Fed will be less accommodative in any upcoming recession than it was in 2020, and that the general trend in interest rates over the next few years is likely to be higher. Whilst this is generally presented as a negative, we see a number of associated investment opportunities. Financial equities, for example, should continue to benefit from a re-rating, as the market realises the significant impact that even small interest rate increases have on their profits. Developed market banks are also in a much stronger financial position than they were before past recessions, which should further support an improvement in valuation. Insurance is another sector we retain exposure to in this environment, with its defensive qualities and ability to benefit from rising interest rates. Elsewhere, we see structural imbalances in many commodity markets, for instance copper or nickel, which present attractive investment opportunities that should withstand headwinds from higher interest rates. We believe investments in these markets have more longevity than simply buying oil and gas equities.

The volatile market conditions at present have served as a reminder of the importance of diversification. Our position in Chinese equities, for example, has generated positive returns this quarter as Chinese shares recovered from depressed valuations. China’s central bank is also easing monetary policy while much of the world tightens, providing a supportive backdrop for the region going forward. This gives us confidence that, despite a potentially challenging economic period ahead, parts of the portfolio can perform well from here. Our investment process is deliberately structured to be benchmark-agnostic and high-conviction, allowing us to divest from an asset class completely if we believe its prospects are poor. This approach has helped us to largely avoid the capital losses in conventional fixed income markets and mitigate some of the falls in equities, and gives us the ability to position appropriately, especially during these difficult times.